Scaling Solutions

Frugal innovation offers low-cost, high-impact solutions

According to a 2022 study published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the mean capitalized cost of developing a therapeutic complex medical device from proof of concept through post-approval stages is $522 million.

For a developing country like Nepal, that’s more than half of the country’s entire health care budget.

Enter, frugal innovation.

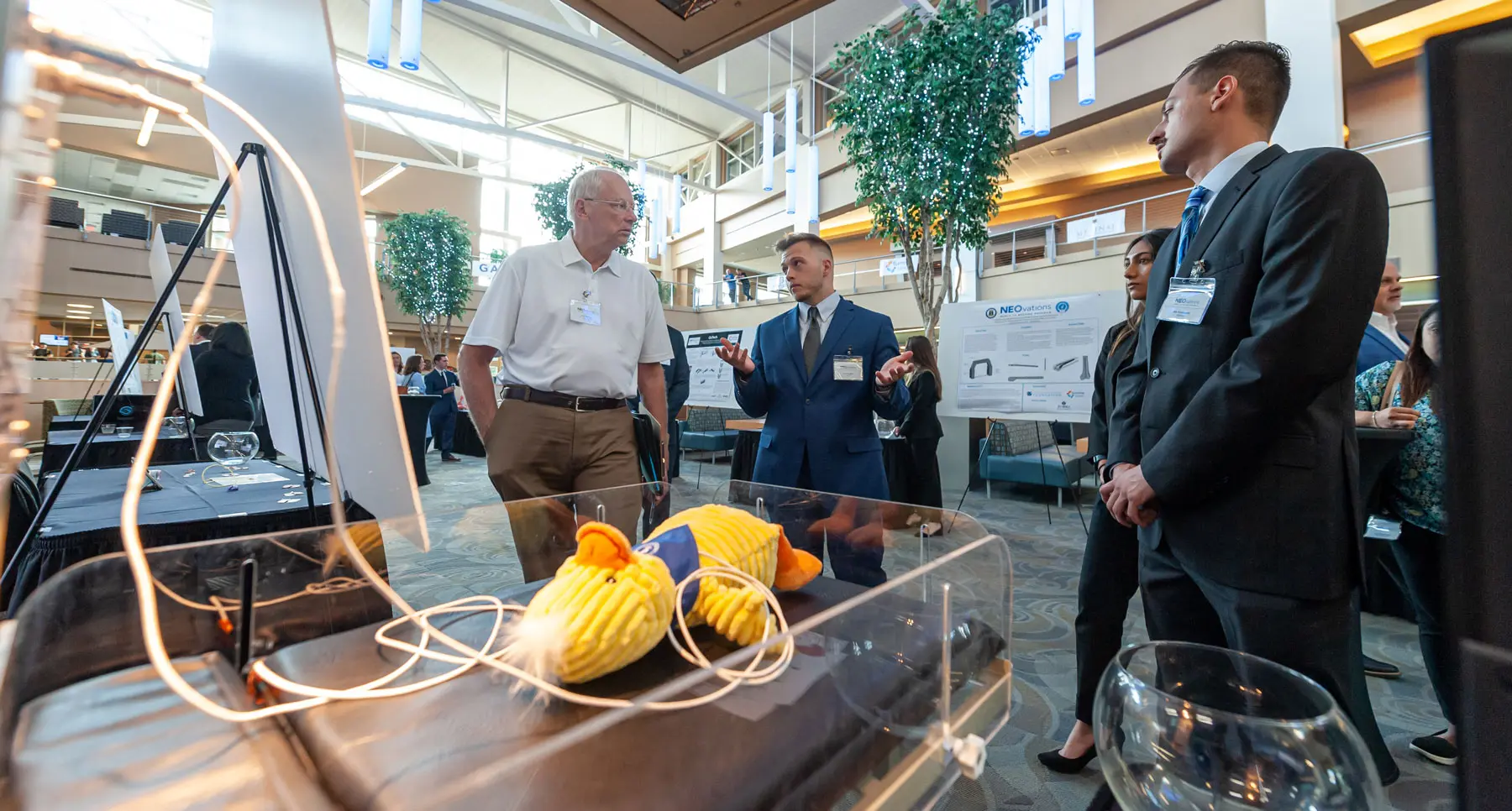

Students from NEOMED worked with physicians from Nepal to test a low-cost baby warmer, which earned the People’s Choice Award in the 2022 NEOvations Bench to Bedside competition.

Frugal innovation provides solutions to medical challenges that are low cost and high impact. As defined by UNICEF, “frugal innovation is born out of necessity and a lack of resources, built by local people with the materials they have available.”

Bernhard Fassl, M.D., director of the Center for Global Health Innovation at Northeast Ohio Medical University, has been working with colleagues in Nepal and other developing countries to address health delivery challenges in low-resourced areas.

“If you look at that traditional biomedical innovation path, that's going to cost you millions and millions of dollars. This is like amazingly expensive,” he noted.

“Frugal innovation is different because you design the prototype or an intervention that can be rapidly integrated into an existing health care system. You integrate it into an existing system with the hypothesis that at the end you're going to be better off. So it’s tested in a real-world system,” Dr. Fassl added.

Projects still need to be vetted and adhere to institutional review board protocols and government regulations. But because frugal innovations are being introduced into existing systems, overhead costs are greatly reduced.

“You need to have a strong scientific foundation. But the other thing you need to have is strong local support,” Dr. Fassl said. “So frugal innovation, especially in global health settings, is not an idea that we impose on our partner countries.”

Because the innovation is developed in partnership with a local system, design concepts are naturally adapted to local needs. An issue or problem has already been identified and the design concepts are created to provide a solution.

“Too often I work with people who have this great idea and even have developed a prototype or a solution, and they're in desperate need of a problem,” Dr. Fassl said.

Frugal innovation provides solutions to medical challenges that are low cost and high impact.

Framework for Innovation

While an innovation may address an immediate need, to make it sustainable and potentially marketable, the innovation needs a framework governed by a quality management system.

“What we do with innovators who have an idea and who have started to work on that idea, we bring them into that structure,” Dr. Fassl said. “So they partly go back [to complete gaps in the process], but then mostly go forward within that existing design pathway. That makes it possible for them to have a product at the end that was developed according to international innovation guidelines that are accepted.”

According to USAID’s Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact, a streamlined framework starts with identification of needs and design, then begins research and development, followed by a plan for introduction, and finally introduction and scale. That framework is explained in the report IDEA TO IMPACT: A Guide to Introduction and Scale of Global Health Innovations.

“Accelerating scale-up by even one year can have a significant impact on lives saved,” the USAID report noted. Similarly UNICEF suggests a four-stage, cyclical innovation process that includes ideation, proof of concept, scale up and product life cycle.

Dr. Fassl provided an example from former medicine students at the University of Utah, where he served as director of the Center for Medical Innovation. The students were on an international rotation in a developing country and encountered numerous cases of women coming in with late-stage cervical cancer. After some investigation, they discovered that the reason cancer was not being treated earlier was the lack of resources – specifically liquid nitrogen used in cryotherapy.

“The way we screen for cervical cancer in low-resourced countries isn't really working. And when we screen, it's difficult to do early intervention just because cryotherapy that is being used to ablate suspicious lesions on the cervix is hard to come by,” explained Dr. Fassl. “That's what inspired them to think of a different solution.”

Their solution? Heat.

“You can cauterize with cold, but you can also cauterize with heat, right?” Dr. Fassl asked rhetorically.

Ultimately, the group developed and tested a heat probe to treat suspicious cervical lesions before they turn into cancer. The device was tested and proved in Zambia and is now sold in 55 countries, mostly low-resourced countries, many of which have added thermal coagulation to treatment guidelines for cervical lesions.

UNICEF suggests a four-stage, cyclical innovation process that includes ideation, proof of concept, scale up and product life cycle

Another example came from Nepal. A group of local physicians had the idea of developing a low-cost infant warmer for premature infants, but they were not sure how to make their idea a reality.

“They really wanted to design an infant warmer that has performance characteristics that match ours, but they didn't know how to do that,” Dr. Fassl said.

The Nepalese physicians partnered with a group of NEOMED students participating in the University’s NEOvations Bench to Bedside program.

“So our contribution was to set up validation testing procedures that would allow them to compare their product to a very expensive Western product. They made incremental improvements as they did testing and changed things as needed,” Dr. Fassl said. “They ended up with an infant warmer that is equivalent in performance to a $35,000 model that is sold here at a production cost of $500 and a retail cost of $1,500 in Nepal.”

Frugal innovation projects like these are part of NEOMED’s global health education activities, many of them supported by the Kiran and Pallavi Patel Foundation, the Dinesh and Kalpana Patel foundation, the Sorenson Foundation and the Crocker Catalyst Foundation.

Learning to Solve Global Health Challenges

Can you teach someone to be innovative?

“There are things you can learn, but you can't teach,” Dr. Fassl said. “A lot of global health needs to be learned but can't be taught. There's no textbook that will teach you about global health so you'll be an expert. The only teachers that you have that are real teachers are the people who you serve. And if you don't go there, you really can't learn. It's the same for innovation. You can read a textbook, but it doesn't make you a good innovator. You just know the rules. The only way you can learn innovation is by doing it.”

Just doing it sometimes results in failure, but Dr. Fassl says that is OK. In fact, he believes that failure is a better teacher than early success.

“I'm almost disappointed when I have students who are successful the first go around because they missed a lot of learning opportunity,” he explained. “I wouldn't even call it failure. You realize that your idea, your thought process, has to evolve to match the needs. Our understanding of the matter evolves over time and so does the solution. You need to give yourself a chance to have your understanding of the matter evolve.”

“I'm almost disappointed when I have students who are successful the first go around because they missed a lot of learning opportunity.”

- Bernhard Fassl, M.D.